|

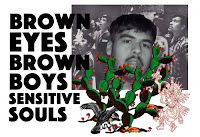

| “brown boys” by florentino diaz |

For much, if not all of my life, I have felt sensitive. I

have felt and “acted” sensitive: tearing up through any emotion, even happy

ones, howling after any scrape, cut, or bruise, and spending too much time

alone with my mother. Of course, “sensitive” was not the word the other boys

were flinging at me. Sensitive was a word reserved for my mother. Sensible, tierno, delicado. And while she

definitely worried about her sensitive son, especially when she wondered about

what kind of man I would grow up to be, it seldom bothered her and she never

hesitated to listen to me cry, even now at twenty-three.

Sensitive is not a fun place to life your life out of at

times. Sensitive, in a world that seems to spin on aggression and competition,

keeps you lonely, it keeps you anxious, and it keeps you vigilant—of your

behaviors, your words, your reactions, and your thoughts. Layering onto that

natural inclination to surveil myself harder came homophobia, racism, and

machismo. Growing up brown, effeminate, and queer brought the harsh magnifying

glass right above my most tender parts and eventually, I trained my own mind to

second-guess itself, to belittle itself, and to never be content with where I

am, but instead to draw happiness from the possibilities of what I could become.

To no surprise I became clinically depressed.

Sensitive is not a fun place to life your life out of at

times. Sensitive, in a world that seems to spin on aggression and competition,

keeps you lonely, it keeps you anxious, and it keeps you vigilant—of your

behaviors, your words, your reactions, and your thoughts. Layering onto that

natural inclination to surveil myself harder came homophobia, racism, and

machismo. Growing up brown, effeminate, and queer brought the harsh magnifying

glass right above my most tender parts and eventually, I trained my own mind to

second-guess itself, to belittle itself, and to never be content with where I

am, but instead to draw happiness from the possibilities of what I could become.

To no surprise I became clinically depressed.

I was lucky enough to enter college around such an

exploratory age—my late teens and early twenties, something many people take for granted. It is at this university

where I began to reconcile my need to express my sensitivity with my desires to

provide myself a career path. Naturally, I was drawn to social movements. Finally, I was living in a reality that was supposed to

validate my struggles as struggles beyond things I needed to “fix” about

myself. Finally, the issue existed outside of me. Finally, there was space for me to be disappointed by life,

shocked by violence, and left in tears by the atrocities I could not seem to

stop focusing on. Finally, my set of skills: communicating hurt, holding

people accountable to their passive/micro aggressions, and doing the emotional

labor of others seemed like it was going to pay off big time; I was going to be

a social worker! Or something…

|

| "untitled" by patricia bordallo dibildox and florentino diaz |

One of those early and very formative places was within the

ideological terrains of Chicanismo. While it seemed a generational thing I

could not fully sync with, I noticed emerging subgroups within the movement

calling themselves Xican@s, Chicanxs, and even Xicanxs that spoke to a more

present-day experience of Mexican American-ness that took time to look at

gender, gender expression, diversity of sexualities, and bodies. But the “new”

Xicanx identity was not very accessible. There simply was not enough writing or

art being shared around that dealt with these “denser” topics as they

intersected with race and nation. The works of these young Xicanxs was kept

archived not across paper, but across slam poetry performances, blogs, art across our

bodies in the forms of tattoos and piercings, within relationships, in dance steps,

and in dreams.

Fortunately, while in school I was able to learn from the

more classic identity: Chicano, as it stood in the sixties and seventies. Now

research savvy, I dove deep into the movement’s history and found an eerie

parallel to my own internal conflict. But before that, I felt “wrong” again.

For such a long time after initially connecting myself to the political

alignment of the Chicano, I was hyper-surveilling myself again. I was host to

thoughts that felt less rooted to me and more connected to an external

understanding I absolutely had to internalize and had no role in creating, much

like masculinity.

All my life older men had made me feel ashamed for trying to

balance and reconcile my emotions and my logic. Older men had chastised me for

not dwelling on values like tirelessness, toughness, sacrifice, order, and

individualism (ego) exclusively. My hopes to be all those things and also be

fragile, whole, chaotic, communal, and compassionate were not allowed in

masculinity. This did not change among the writings, histories, and narratives

of the popularized Chicano movement. Again, I found myself in a space full of

men, this time with my peers and some elders that romanticized militancy, legal rights,

and logic to pursue their idea of liberation.

It was not until I stumbled across intersectionalism that I

began to see that eerie parallel I mentioned early. Intersectionality, and by

extension the works of legendary and contemporary radical poets and feminists

of color, often queer Black women, gave me a new insight into myself that I am

eternally grateful for. I began to believe in an authentic self. I began to

understand the bigger picture of what it means to be Ramiro and in that

overwhelming experience, I noticed the complexity of the self, but also how the

self is a mirror or microcosm of social movements. It became apparent that

mining my past for insight and making peace with said past would help me return

to a life that takes place in the moment. After all, for me, anxiety has never

been anything but an obsessive fixation on the future with shame and guilt

shooting up from the past, barring me from sacredness of the moment.

Just like that, “Chicano” became “Ramiro”. I saw the

movement much how I saw myself: an amazing force thirsty for freedom, but with

skills unbalanced and emotional creativity undeveloped. That lack of balance

came from self-sabotage. It came from refusing to listen to the ways my logic

and emotions naturally reconciled themselves within me, from refusing to be

patient, from refusing to be my complete self in everything that I do, and from

refusing to be intuitive. But it did not always feel like self-sabotage because

it was rewarded so often. I experience a much easier life, filled with far more

opportunities for me to be remembered as "important", all because I man. In

other words, because the Chicano movement’s foundation was created almost

exclusively by men as a result of their fear for all things feminine within

themselves (and by projection, women), the movement fell into fragility so

quickly after its prime as a result of sabotage, a lot like myself in later college years.

Author bell hooks refers to this self-sabotage psychic self-mutilation. “The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.”

Like all people working against the system, movements also

fall into states of fragility and depression. But when faced with fragility,

the best thing one can do is to feel it through and through. To learn from it. To

embrace this cyclical flow between abundance and scarcity of energy, as is the

flow of the seasons, as is the flow of self-care. But without any voice to lead

that healing, without anyone to validate that importance of breaking before

rebuilding again (to winter and then spring), the movements became a massive

vehicle of community harm, notably at the expense of women. However, it was not

that those experts on healing, wholeness, and transgression were not there, it

is that they were not welcome. Queer men, women in general, non-binary people,

Black Chicanos, or anyone that wanted to focus on the present issues (sexism

included) were preferably unheard and excluded from the movement that was too deep into its long-term goals. So, the

Chicano body could not hear itself because it artificially segmented itself

instead of doing the hard work it takes to deal with everything the body needs. In the case of Chicanismo, sexism and sexual pleasure were ignored despite being vital to the true collective, among other issues.

Professor Cotera’s project then becomes a metaphor for

therapy in my eyes. I see the work of digital archives as something like giving

one’s self therapy through honesty. But, instead of individual experiences, the

pieces we must reassemble for this act of macro self care are whole stories of

people, as people, not events, represent and carry the collective memory of the

Chicano movement. In collecting these incredibly necessary oral histories we

are beginning to make peace with our past as Chicanos. We are learning that

time is in fact not linear, and that the past has as much to be planned for as

the future, for there is no chance at living a liberated tomorrow without

coming back to the present and being content—being happy, well nourished, and

critical Chicanos before objects of activism.

I enrolled in professor Cotera’s class to learn more about my

process and myself, as much of it is still extremely confusing. I enrolled

because Cotera is providing a safe and effective model for us to practice

history reunification, reconciliation between the emotional and logical, a

balance that does not live in camps of masculine and feminine, but inside each

of us, all the time. I enrolled to thrive as sensitive, to embrace my uniqueness and reorient myself into the true Chicano movement, which I believe is more accurately the Chicana movement.

In healing the Chicano movement, in healing myself, I hope

to discover the true nature of the Chicano movement and its sensitive side. Which, with each passing

day of this class, seems that it was clearly carried on the backs of gender and

sexual minorities. We are essentially redefining Chicano by bringing the movement

closer to its roots through memory recollection. We are not comparing, “bettering”,

or perfecting anything. We are simply trying to be authentic in how we heal from the trauma we inflected on ourselves, which is a trauma often learned outside ourselves and through the toxic systems of sexism, racism, and imperialism. And that is a

lesson that will extend far beyond the classroom. This is the lesson of

recovery.

|

| “these great divisions hurt me but i’ll find home again” by florentino diaz |

I love the connections you make between the personal, the political, the scholarly, Ramiro. I am especially energized by the idea that through recovering the voices of those long ignored, we might "heal the split" (to paraphrase Gloria Anzaldua) between the liberatory potential of the Chicano movement and its failures--to sufficiently love, to let live, to know itself authentically. This phrase you use "healing the Chicano movement" is so evocative, as is your reading of "recovery."

ReplyDelete